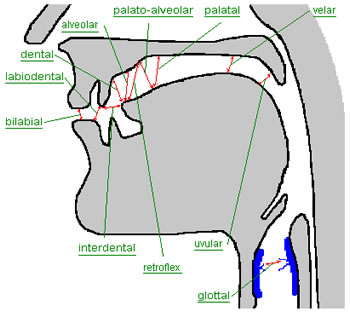

ArticulationIn all the languages of the world, linguists can’t agree how many different consonances exist. Some say there are around one hundred, and others say there are over one hundred twenty. The disagreement comes from where to draw the distinction between the consonances that are similar. The consonant "T," for example, is quite different from language to language. In French "T" is pronounced with the tongue very forward in the mouth on the back of the upper front teeth, in English the "T" is placed on the rim of the gum behind the upper front at the point just before it rises up to the roof of the mouth, and in Chinese the "T" consonant is made high on the roof of the mouth; all are quite different in the way they sound.

Consonants of speech have been used successfully for a very long time in teaching brass instruments; every brass player has learned to start a note with "Ta," "Da" or an occasional "Ka," but in fact there is a huge difference between consonants in speech and articulation on brass instruments. Nature created our vocal mechanism in a very wonderful and functional way; the sound source comes first and the consonant and vowel (articulation and tone color) mechanisms come second. It works beautifully. The sound from the larynx reaches the mouth and with vowel sounds and consonances we have an infinite possibility of sounds, in fact, we have language. But what happens when the articulation mechanism (the tongue) comes first and the sound source (the lips) come second? The results are so different that comparisons can be dangerous or at least difficult. Still, most of our references to playing brass instruments come from vocal concepts. I was very surprised in 1990 when performing and recording Verdi’s Il Trovatore with the Maggio Musicalli di Firenze and Luciano Pavarotti singing the lead. I was amazed to hear Pavarotti vocalizing (warming up) on one of the exercises in my book. An exercise I, of course, took and modified from the famous Stamp trumpet book and which Stamp, of course, took from the very copious repertoire of vocal exercises. I was hearing this exercise in its original form for the first time. These exercises work for us and will continue working for us, but there are a few points of the differences between vocal and brass that need to be addressed. Do those vocal consonants that we use when we first learn how to make a sound on our instruments really work for brass? What is the difference between "Ta" and "Da?" "Ta," is what linguists call a nonvocalized plosive. First comes the sound of the consonant (articulation) then the sound of the vowel (tone); this works very well on a brass instrument. But "Da," the articulation that we are taught to use for a softer attack is a vocalized plosive, quite a different situation. With "Da," first the vocal sound comes and then the consonant. That is not possible on a brass instrument, except if we articulate after already playing a note. "Ta" and "Da" have nevertheless worked well to guide brass

students to discriminate different articulations, but they are very limited

in their scope. There are four aspects to articulating on brass instruments,

and when a player can coordinate those four things our capacity for a wide

spectrum of articulations is enormous. The four aspects are: Of course, airflow at impact is determined largely by dynamic and register, the lower and the louder requiring greater air flow. Sometimes the low register, especially on tuba, requires a huge volume of air. There is no human function that demands the movement of such airflow as playing tuba in the very low register. Air pressure is very connected to airflow but is differentiated by the resistance when the air meets the embouchure. That resistance together with the airflow and time span broadens even more the articulation verity potential. Tongue placement modifies attack in a very important way. Like the different "T's" mentioned in the first paragraph, tongue placement changes the articulation from a clear instant attack when it is forward and a less instant attack with the tongue further back in the mouth. It should also be said that generally the low register usually responds better with the tongue very forward, even between the lips and in the higher register, to avoid being too abrupt, works better further back in the mouth. The compression of air behind the tongue at impact determines the sharpness of the attack. Suddenly the potential becomes evident. Air impact on an attack would be used for a fp, and air compression behind the tongue would be used for an accent! But when is it clearly just one or the other? What is the mix if we want to make an accented fp or a pesante accent? This is only a very small variable when you think of the possibilities of these four aspects of articulation. Now come two tasks: learning to use these articulation functions and far more importantly, which mix of the four possibilities should we use. With essentially an infinite number of possibilities these articulations need to be on demand from the information that your minds ear and your musicality dictate; this is one of the many reasons for listening to music of all kinds. The more we know, the more we have experienced, the more sonic vocabulary we have to call upon for expressing our own individual musicality. The only danger is that we must avoid learning one or two ways of articulating and dogmatically continuing using only the articulations we have learned and are familiar with. Something should be said about starting a note without using the tongue at all. That can occasionally be a good therapy for correcting poor response but as a normal day-to-day articulation it is very limited. Articulation is the fine-tuning of rhythm and most of the time the energy of the music requires it be focused and clear. In language when we are unclear with our consonants we have a tendency to sound either drunk or stupid, we all know that sound! But when clear consonants are returned we can give the impression of intelligence! It’s very much the same with musical performance particularly in lower instruments. The human ear hears less clearly in low registers, therefore we who play in those low registers need to make a special effort in articulating clearly. Music becomes more enjoyable to play and to hear. As William Bell used to say for his goodbyes, “Tatakatut” Hiroshima, Japan, January 22, 2006 |

But if we can agree that there are over one hundred consonances in Languages,

and if we can agree that articulation is the consonance of the musical language,

then how many types of articulation are there in music? And much more specifically,

how many types of articulation do we have the possibility of producing on brass

instruments?

But if we can agree that there are over one hundred consonances in Languages,

and if we can agree that articulation is the consonance of the musical language,

then how many types of articulation are there in music? And much more specifically,

how many types of articulation do we have the possibility of producing on brass

instruments?